June 2015

REGULATORY DEVELOPMENTS

Review of Standardized BOLI RWA Reporting for Q1-2015

The first quarter of 2015 marked the initial reporting period for banks under the U.S. Basel III Standardized Approach. As we’ve reported previously, the regulators have provided specific instructions for reporting BOLI RWA in the applicable form (Schedule RC-R). Of note, Schedule RC-R includes specific line items for the carrying value and aggregate RWA of separate account (SA) and hybrid BOLI. The instructions also direct institutions to include stable value protection (SVP) and general account exposures to SA BOLI (e.g., DAC and mortality reserves) in the SA BOLI line items on this schedule.

In reviewing the Q1 values reported by the 500 largest banks and 500 largest bank holding companies, we noticed a number of potential issues. Please note that the populations reported on below are independent of one another. In other words, banks that are in the top 500 may not have a corresponding BHC that is in the top 500.

| Top 500 (Total Assets) | Institutions with Greater than $10 billion in assets | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banks | BHCs | Banks | BHCs | |

| Number of Institutions in Group | 500 | 500 | 112 | 74 |

| Percentage of institutions that reported SA and/or Hybrid BOLI on the Other Assets schedule but did not enter values in applicable line items in Schedule RC-R | 32% | 38% | 21% | 32% |

| Subgroup: Hybrid BOLI only | 48% | 55% | 13% | 13% |

| Subgroup: SA BOLI only | 23% | 23% | 25% | 25% |

| Subgroup: Both SA and Hybrid BOLI | 29% | 22% | 62% | 62% |

| Institutions that reported aggregate carrying values on Schedule RC-R that were less than the carrying values on the Other Assets schedule* | 8% | 7% | 17% | 19% |

* Based on the instructions, we would expect the carrying values to be slightly larger on Schedule RC-R since they are supposed to include SVP, DAC and mortality reserves

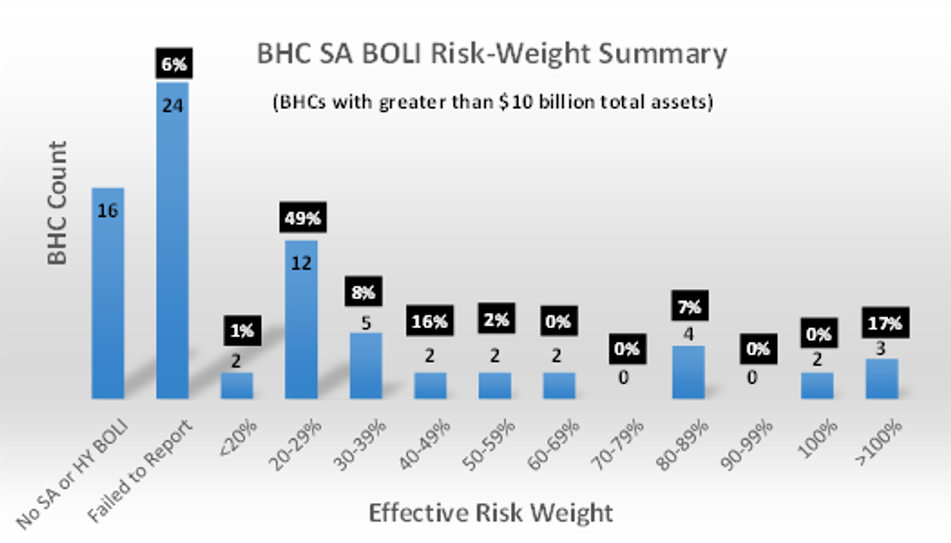

Despite the potential issues that will need to be ironed out in the coming quarters, the line items allow for an analysis of the reported effective overall RWA of SA BOLI programs.

The charts below show the number of institutions whose effective overall SA BOLI risk weight fell within certain ranges. We also show the percentage of the total reported SA BOLI carrying value that each range represents.**

** The percentage of the total reported SA BOLI carrying value for banks that did not report SA BOLI on Schedule RC-R is computed as the sum of Hybrid and SA BOLI on Schedule RC-F divided by the total Hybrid and SA BOLI reported on Schedule RC-F. For all other categories, the denominator was the aggregate carrying value reported on Schedule RC-R.

Finally, we show scatter plots of SA BOLI and Effective Risk Weights for the institutions with the largest reported SA BOLI programs.

Banking Regulators Finalize Revisions to Advanced Approaches Capital Rules

On June 16, the OCC, FDIC, and Federal Reserve finalized revisions to the advanced approaches capital rules. We had reported on this proposal in our December LRA update. Only two comment letters were submitted and the rules were largely adopted as proposed.

The final rule updates certain aspects of the advanced approaches rule, including calculation requirements for wholesale exposures and derivatives, among others.

The final rule will be effective October 1, 2015.

OTHER DEVELOPMENTS

IRS Updates Audit Guide for Non-Qualified Deferred Compensation Plans

On June 9, the IRS published an updated audit guide for Non-Qualified Deferred Compensation (NQDC) Plans. According to a Groom Law Group memo, this was the first update since February 2005. The following areas are identified as priorities:

- Examining constructive receipt and economic benefit issues;

- Examining the employer’s deduction;

- Examining employment taxes (including income taxes and FICA/FUTA); and

- Examining compliance with Section 409(A).

The audit guide is fairly brief and high level, but may provide a useful overview of key areas that an IRS examination is likely to investigate.

IRS Prevails in Tax Court re Investor Control Violation under High-Net-Worth Private Placement Variable Life Insurance

On June 30, the U.S. Tax Court ruled in favor of the IRS in a matter contending that a venture capitalist (Jeffrey Webber) who owned private placement variable life insurance should be treated as the owner of the underlying assets based on the “investor control” doctrine. According to the ruling, the policy owner indirectly controlled the investments in the separate accounts, which invariably were made in companies that the policy owner had intimate knowledge of and financial interests in.

Below is a description of how the investment decisions were recommended to the separate account’s investment manager:

Mr. Lipkind [policy owner’s attorney] explained to petitioner [policy owner] that it was important for tax reasons that petitioner not appear to exercise any control over the investments that Lighthouse [insurance company], through the special-purpose companies, purchased for the separate accounts. Accordingly, when selecting investments for the separate accounts, petitioner followed the “Lipkind protocol.” This meant that petitioner never communicated—by email, telephone, or otherwise–directly with Lighthouse or the Investment Manager Instead, petitioner relayed all of his directives, invariably styled “recommendations,” through Mr. Lipkind or Ms. Chang [policy owner’s personal accountant].

The record includes more than 70,000 emails to or from Mr. Lipkind, Ms. Chang, the Investment Manager, and/or Lighthouse concerning petitioner’s “recommendations” for investments by the separate accounts. Mr. Lipkind also appears to have given instructions regularly by telephone. Explaining his lack of surprise at finding no emails about a particular investment, Mr. Lipkind told petitioner: “We have relied primarily on telephone communications, not written paper trails (you recall our ‘owner control’ conversations).” The 70,000 emails thus tell much, but not all, of the story.

The Court’s decision included an analysis of the “investor control” doctrine, including the following brief description of IRS Revenue Ruling 2003-91:

The IRS stated its assumptions that: (1) the policyholder “cannot select or recommend particular investments” for the subaccounts; (2) the policyholder “cannot communicate directly or indirectly with any investment officer * * * regarding the selection * * * of any specific investment or group of investments”; and (3) “[t]here is no arrangement, plan, contract, or agreement” between the policyholder and the insurance company or investment manager regarding “the investment strategy of any [s]ub-account, or the assets to be held by a particular sub-account.” Rev. Rul. 2003-91, 2003-2 C.B. at 348.

In short, although the policyholder had the right to allocate funds among the subaccounts, all investment decisions regarding the particular securities to be held in each subaccount were made by the insurance company or its investment manager “in their sole and absolute discretion.” 2003-2 C.B. at 348. Under these circumstances, the IRS concluded that the insurance company would be treated as owning the assets in the separate accounts for Federal income tax purposes. The IRS indicated that this ruling was intended to “present[] a ‘safe harbor’ from which taxpayers may operate.” 2003-2 C.B. at 347.

Ultimately, the court identified the following “key incidents of ownership”:

- The power to decide what specific investments will be held in the account;

- The power to vote securities in the separate account;

- The ability to exercise other rights or options relative to these investments;

- The ability to extract money from the account by withdrawal or otherwise; and

- The ability to derive, in other ways, what the Supreme Court has termed “effective benefit” from the underlying assets.

The Tax Court ruled that the IRS rulings enunciating these principles deserve deference. The ruling went on to explain that records clearly indicate that Mr. Webber enjoyed each of the key incidents of ownership.